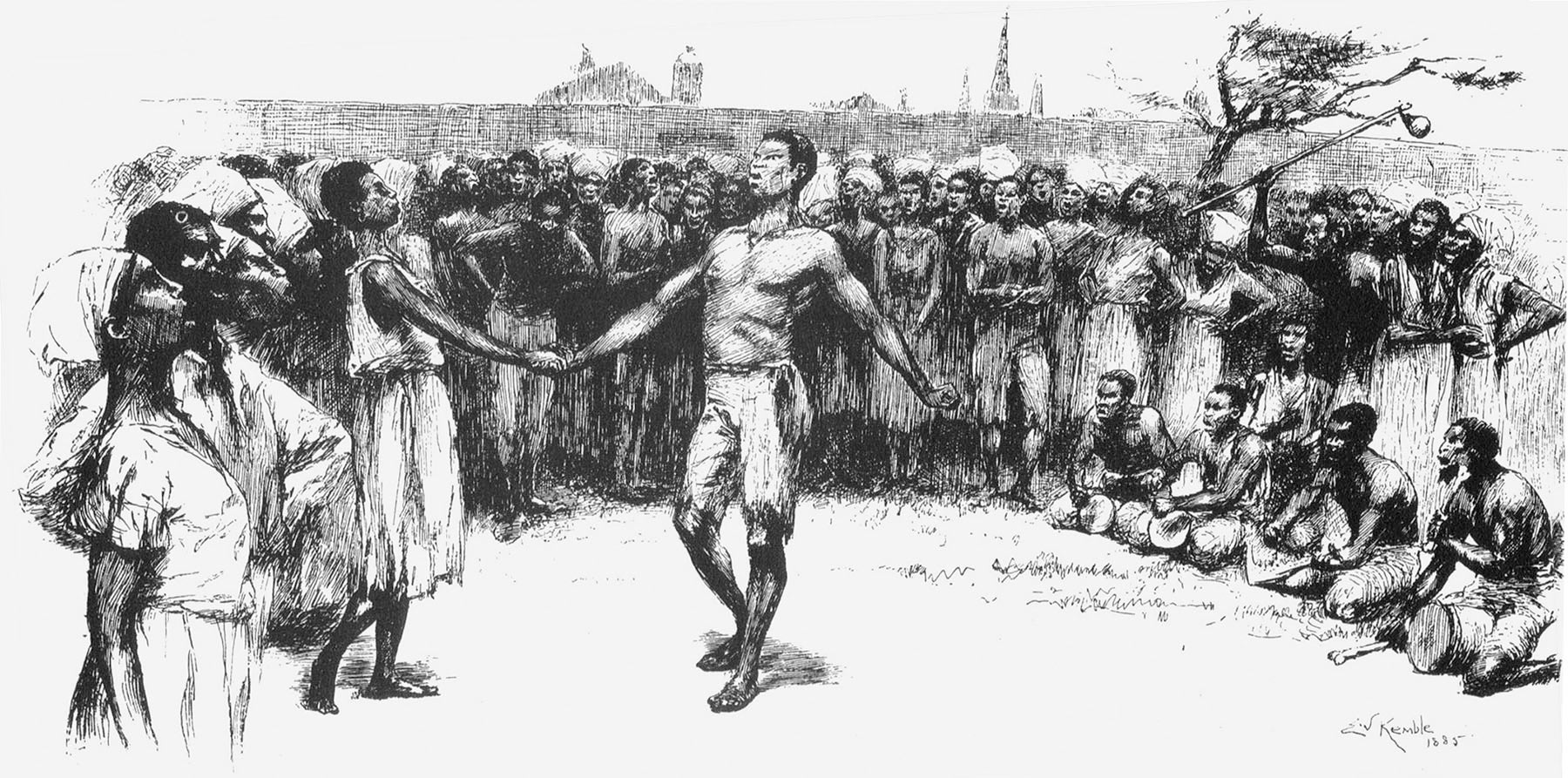

In the second section, Mustakeem focuses on slave transport, particularly at their main nodes in West African port cities, where European slave traders would first meet and purchase their captives. She considers the terrible fact that by the mid-1900s, this cruel culture had enabled the kidnapping of over two-thirds of the already enslaved. She analyzes the money and power-driven mentality that brought ships to African territories to purchase people who had been ripped from their homes to facilitate white European colonization. In the first segment, warehousing, Mustakeem quickly makes clear that the term is meant as an ironic euphemism for violent enslavement. She utilizes modern language for describing commodity goods operations, naming them warehousing, transport, and delivery. The book breaks down this production of humans as commodities into three stages. She highlights people whom the slave trade “forgot,” arguing that the commodification of African bodies helped their owners rationalize and systematize their sale and abuse.

Mustakeem proceeds to explore how the prevailing narrative describing the passage of youthful and able-bodied people into lifetimes of slavery in new lands unforgivably marginalizes slaves who did not fit in this category. To produce a new historicism of this time, Mustakeem contends, scholars must acknowledge the elliptical truth of the slave narrative, and the consequence that little can be recovered in the form of language. Any attempt to resolve the stories of slaves who suffered, often alone, is necessarily reductive, relying on emotional tropes such as those of being demoralized, of suffering, of alienation. Rather, the transatlantic slave experience was multiple. She argues that, contrary to common narratives, slaves did not really have a shared experience of this time. Mustakeem begins with an introduction in which she lays out her framework for thinking about the Middle Passage.

In doing so, she analyzes the erasures that are endemic to the act of historicizing the experience of mass atrocity. Rather than look at the displacement of Africans from a statistical, economic, or otherwise quantitative view, Mustakeem validates their individual narratives, exploring and humanizing their uniqueness. African-American historian and professor Sowande Mustakeem’s Slavery at Sea (2016), is both a historical analysis and theoretical revision of the tragic trafficking of black bodies in the eighteenth century, a time when no legal recourse existed enshrining their basic rights or offering recourse for their suffering.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)